In every nook and corner of Tamil Nadu, from the bustling markets of Madurai to the quiet village shrines tucked between coconut groves, one figure stands with grace, familiarity, and silent wisdom—Ganesha. Known affectionately in Tamil homes as Pillaiyar, this elephant-headed deity is more than just a remover of obstacles; he is the cherished first deity we turn to, the guardian of beginnings, the symbol of intellect, and the bearer of deep spiritual metaphors. But have we paused to ask—why the elephant head? Why the potbelly? What deeper meanings does the Tamil tradition attach to this most beloved of gods?

Let’s journey together into the heart of Tamil Hindu tradition and unravel the rich layers of symbolism behind Ganesha’s form—especially as Lambodara, the large-bellied one.

The story of Ganesha doesn’t begin in abstraction—it begins with the tender hands of a mother and the gentle breath of creation. In countless Tamil homes, this tale is one of the first stories whispered into the ears of children, often while they sit cross-legged on their grandmother’s lap or lie under the soft whirr of a ceiling fan on a lazy afternoon. It is a story not merely told, but felt—with warmth, with wonder, and with a deep emotional connection that spans generations.

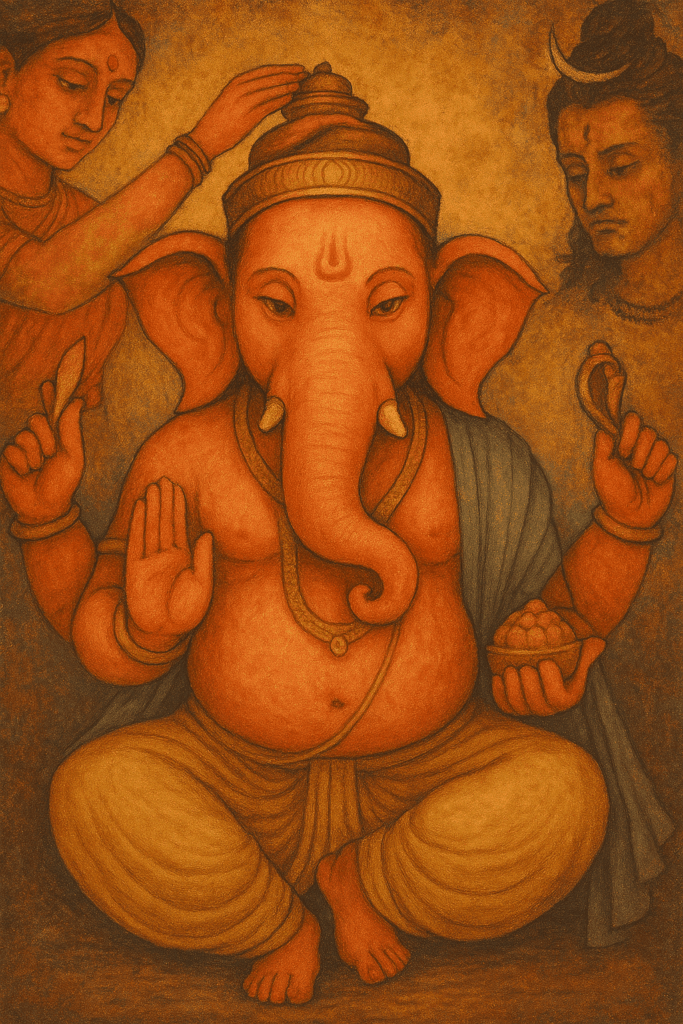

Parvati, the goddess and divine mother, yearning for companionship while Shiva was away in deep meditation, decided to create a child. Using the fragrant paste of sandalwood from her bath, she shaped a small boy, perfect in form, and with her divine breath, infused him with life. This wasn’t just an act of creation—it was an act of pure love. Ganesha, born not of fire or fury, but of maternal affection, stood as a guardian outside her chamber, dutiful and firm, when Shiva returned unexpectedly.

What followed was a misunderstanding, tragic and immense. Not knowing the boy was his own son, Shiva, angered by being denied entry, severed his head in a single stroke. The moment of destruction is narrated with hushed awe in Tamil retellings—not to instill fear, but to reveal the fragility of even divine bonds, the consequences of ego and haste.

But the story does not end in sorrow. It moves, like life often does, toward reconciliation and renewal. When Parvati’s grief shook the heavens, the gods scrambled to make things right. A new head was found—the head of a wise elephant, symbol of memory, strength, and understanding—and placed upon the lifeless body. With mantras and divine will, Ganesha rose again.

He was no longer just a child made of paste, but a god of immense power, wisdom, and grace. The elephant head was not a mistake—it was destiny. From that moment, Ganesha became Vinayagar, the remover of obstacles, the lord of beginnings.

But in Tamil Nadu, this story is never told just as a divine drama. It is always more than mythology—it is a lesson tucked within layers of emotion. It teaches obedience through Ganesha’s devotion to his mother, consequence through Shiva’s act, and above all, transformation through his rebirth.

Every element of this story speaks to the Tamil way of seeing life—not in black and white, not in right or wrong, but in journeys, in growth, in learning through hardship. Ganesha’s beheading is not merely a violent act—it is a symbolic shedding of the ego. And his resurrection is not just a miracle—it is the eternal promise of second chances.

And so, in this retelling, Ganesha is never distant. He is not simply the deity at the temple altar. He becomes an emotional anchor in Tamil life—a gentle guide who has known pain, who has walked the path of sorrow and emerged with grace. A god with a belly full of patience and a head full of wisdom, born of love, shaped by loss, and reborn into divine purpose.

That is the Ganesha Tamil hearts hold close—the child of Parvati, the misunderstood guardian, the elephant-headed lord of compassion, and the ever-present protector who stands silently at every threshold, reminding us that even broken beginnings can bloom into sacred destinies.

In Tamil, Ganesha is affectionately known as Pillaiyar—a name that means “noble child.” But it means far more than what the translation suggests. It’s a name that softens the divine, that brings godhood closer, into the folds of everyday life. Unlike the grand and distant Sanskrit titles like Vighnaharta (remover of obstacles) or Vinayaka (the knowledgeable one), Pillaiyar feels personal. It’s the name you’d call out not in ceremony, but in comfort—like calling a beloved member of your own household.

And that’s exactly what he is in Tamil homes—not just a god, but family.

He is the one who quietly sits at the threshold of houses, molded out of clay, sometimes placed under the cool shade of a neem tree, adorned with just a smear of sandalwood, a few grains of rice, a bit of turmeric, and a flower plucked from the garden. There’s no grandeur in this offering, only sincerity. And that is enough.

From the first cry of a newborn to the first letter traced on a bed of rice during the Vidyarambham ceremony, Pillaiyar is there. He is present at weddings, before business deals, during the laying of foundation stones, and even before cooking a festive meal. His presence is the seal of blessings, the sign that things are starting on the right note.

He is the guardian of beginnings—not by decree, but by trust. Tamil hearts don’t just worship him—they lean on him.

In this way, Pillaiyar becomes more than a name. He becomes a feeling—a blend of reverence, affection, and cultural memory that lives quietly, gently, in the rhythms of Tamil life.

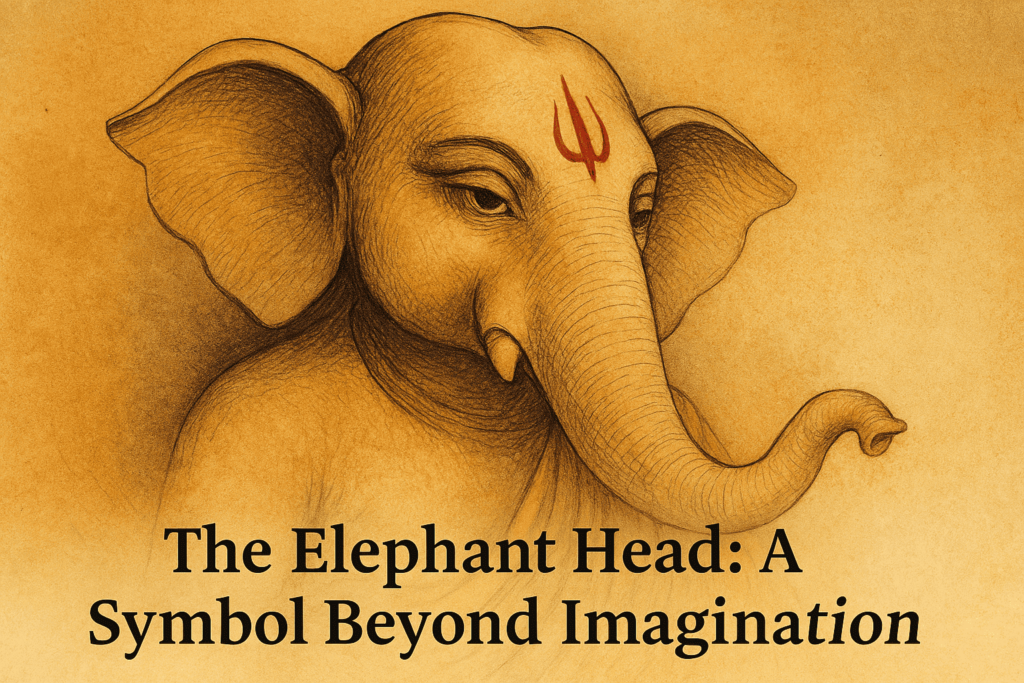

Why an elephant?

To the casual eye, Ganesha’s elephant head might seem unusual—charming, yes, but curious. Yet in Tamil tradition, this form is not fanciful; it is profoundly intentional. The meaning behind it runs deep, as deep as the ancient forests where elephants tread with quiet confidence.

In Tamil culture, the yaanai is no ordinary animal. It is revered. Its sheer strength commands respect, yet its nature is never violent. Elephants are thoughtful, tender with their young, respectful of elders, and known for their long memory. They are leaders, not by dominance, but by example. These traits are not just admired—they are idealized. And so, when Ganesha wears the elephant’s head, he is not just unique—he is complete.

He becomes a symbol of gnanam—wisdom that listens more than it speaks, understands more than it explains. His large ears suggest that true intelligence comes from listening deeply. His small eyes reflect sharp focus, and his curved trunk, with its precision and strength, becomes a metaphor for adaptability in thought and action.

Across Tamil temples, elephants are carved at gateways, standing sentinel at the entrance to sacred spaces. They are not just decorative—they represent strength under control, protection without aggression. And just like those temple guardians, Ganesha too stands at the threshold of our lives, blessing our beginnings and guarding our journeys.

But perhaps the most touching symbolism lies in the way elephants move through the forest. They do not bulldoze their way forward. They feel the land, sense the path, and gently push aside the undergrowth to create a way for others to follow. In this graceful act, we see the truest form of Ganesha as Vighnaharta—the remover of obstacles. He doesn’t destroy the difficulties in our lives with fury; he simply guides us around them, just like the wise elephant in the wild.

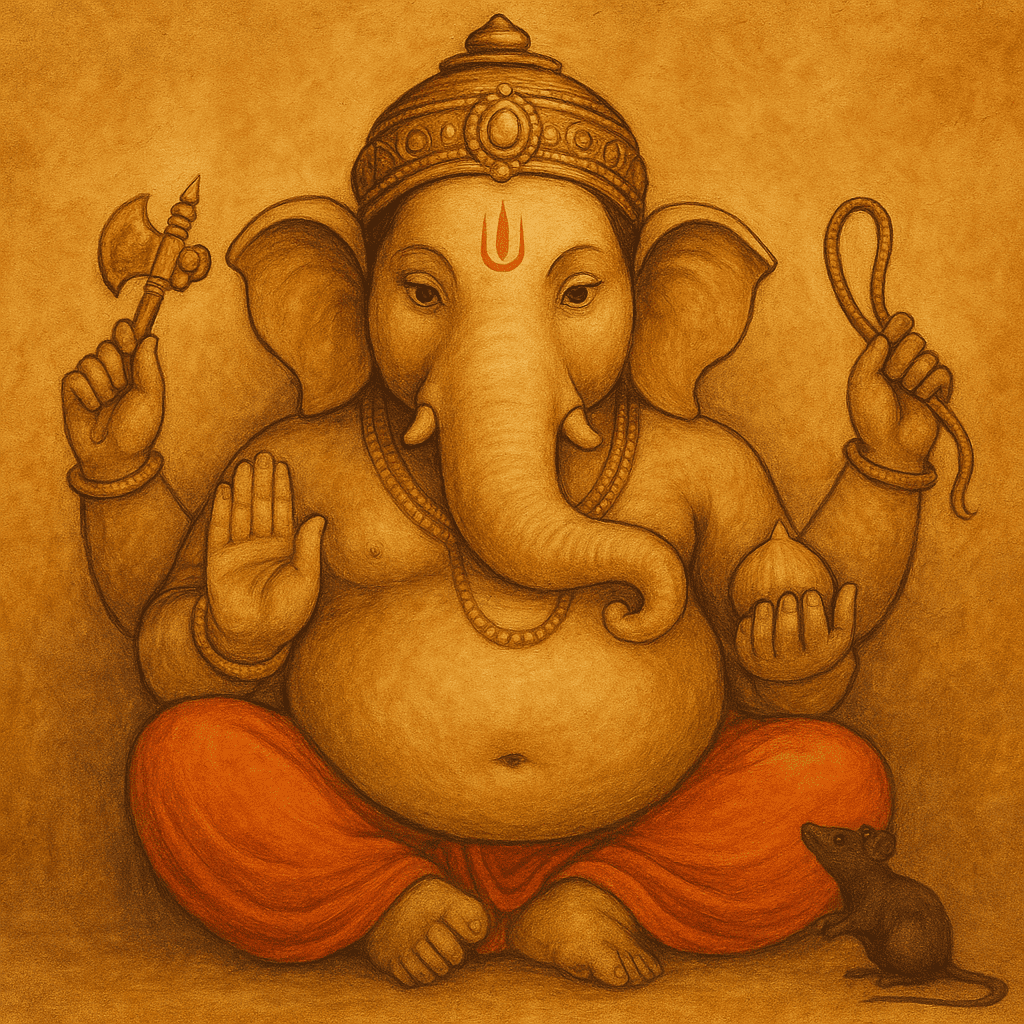

Among the many features that define Ganesha’s unmistakable form, one of the most curious—and quietly profound—is his large, round belly. In Tamil culture, this isn’t an oddity. It’s a beloved symbol. He is affectionately known as Lambodara—lambu meaning hanging, and udaram meaning belly. The name itself rolls off the tongue with a sort of tender reverence, as though describing someone close and familiar, not distant and divine.

But it invites a question: why would a god have a potbelly? Shouldn’t divinity be flawless, sculpted, ideal?

And that question, simple as it may seem, holds the doorway to deeper understanding.

Because Ganesha is not the kind of god who stands aloof in perfection. He is the god who reflects the human journey—its fullness, its messiness, its quiet strength. His belly is not about indulgence. It is about containment.

The large belly represents his infinite capacity to hold. Joy and sorrow, failure and success, devotion and doubt—everything finds a place in Lambodara’s womb-like center. He digests the world, not just physically, but emotionally and spiritually. Like a wise elder who listens more than he speaks, Ganesha absorbs the chaos without letting it tip his balance.

In Tamil bhakti poetry and village folk songs, this image is often painted with warmth. The poets don’t see his belly as excess—they see it as grace. To them, Lambodara is the one who can stomach the bitterness of the world and still smile with kindness. The one who carries the universe in his gut and still sits in stillness.

There’s even a quiet humor in how he’s described—playfully plump, yet supremely poised. This blend of joy and seriousness, of softness and strength, is what makes Lambodara so relatable. He teaches us that true divinity isn’t about rejecting the mess of life, but about embracing it fully, and staying grounded through it all.

So when the world overwhelms, when burdens feel too heavy, Tamil hearts turn to Lambodara—not to escape, but to learn. To remember that one can carry sorrow without bitterness, joy without pride, and motion without losing stillness.

Ganesha does not just sit with a belly full of sweets—he sits with a belly full of life.

Among all the visual cues that make Ganesha instantly recognizable, one detail often invites a second glance—his single tusk. One long and curved, the other, conspicuously missing. It may seem like an imperfection at first, but in Tamil tradition, it is a feature that glows with meaning.

Many stories float around about how Ganesha lost his tusk—some speak of fierce battles, others of playful adventures. But in the Tamil telling, there is a quiet, noble gravity to the tale. It is not a story of violence, but of wisdom, patience, and a sacrifice made for the sake of something greater.

It begins with the sage Vyasa, who wished to immortalize the Mahabharata—not just a story, but a spiritual ocean of knowledge, duty, and human emotion. He needed someone not only to write, but to understand. Someone who could keep pace with a divine narrative. He turned to Ganesha.

Ganesha agreed, but with a condition: Vyasa must recite without pause. The moment he hesitated, Ganesha would stop writing. Vyasa, shrewd and wise, accepted, occasionally weaving in complex verses to slow the rhythm and gather his thoughts. But Ganesha, determined and deeply committed to the task, did not falter.

Then came a moment when his writing instrument—perhaps a quill, perhaps something crafted from divine wood—broke. For any other scribe, that would have been the end of the session. But not for Ganesha. Without hesitation, he snapped off one of his tusks and continued. The story had to be told. The words had to flow. The moment had to be honoured.

And so, the tusk was not lost. It was offered.

This act, simple and silent, reveals the essence of Ganesha’s spirit — aikkya buddhi, the unity of mind and purpose. It also reflects a deeply Tamil concept: thannilai—the noble ability to put one’s personal comfort aside in service of a higher calling. Whether it’s in a poet sacrificing sleep to finish a verse, a mother skipping meals to feed her child, or a worker pushing through pain to meet a promise, thannilai lives in everyday Tamil life. And Ganesha, with his broken tusk, stands as the divine embodiment of it.

The missing tusk, then, is not a defect. It is a divine reminder that sacrifice, when made for truth, for duty, for knowledge—it sanctifies. It beautifies. It elevates.

So when we see Ganesha’s asymmetrical smile and single tusk, we don’t see damage—we see devotion. We see a god who didn’t cling to perfection but chose purpose instead.

Before the first word is written, before ink meets paper, before even thought fully forms into language—there is a curl.

A gentle, spiral stroke, small and unassuming, drawn in a single motion by the hand that holds the pen. This is the Pillaiyar Suzhi—a sacred squiggle that quietly declares, “Let this begin well.”

In Tamil culture, this symbol is more than a flourish. It is a gesture, almost like a bow. It represents the curved trunk of Ganesha, the ever-present guardian of beginnings. To draw the Suzhi is to invite Pillaiyar into the space—not just into the document, but into the intention behind it.

Children are taught to write it even before learning the alphabet. A notebook for school, a ledger in a shop, a piece of art, even a simple birthday card—everything begins with that curl. It doesn’t matter if one is writing a poem, a grocery list, or an architectural plan. The act of beginning itself becomes sacred.

This is not superstition. It is reverence woven into daily life.

It reflects something deeply Tamil—a worldview where the divine is never separate from the ordinary. Where divinity does not sit on a distant pedestal, but moves with us, eats with us, lives among us. And what better way to express that than by starting every expression of thought, however humble, with Ganesha’s graceful mark?

The Pillaiyar Suzhi is silent, yes—but it speaks. It says: May my thoughts be clear. May my efforts bear fruit. May I have the strength to complete what I begin.

And so, with just a curl of the wrist and a whisper of intention, Tamil hands begin again and again, always with Pillaiyar, always with hope.

One cannot speak of Ganesha in Tamil tradition without invoking the vibrant spirit of Vinayagar Chaturthi—a time when devotion takes on color, sound, scent, and celebration. While cities like Mumbai may be famed for their towering idols and grand processions, Tamil Nadu’s observance of the festival is a more grounded and intimate affair—rooted in homes, neighborhoods, and quiet rituals passed down through generations.

In temple towns like Tiruchendur, Kumbakonam, and Madurai, the air grows fragrant with incense and turmeric. Artisans lovingly mold clay Pillaiyars by hand, shaping each with care and placing them in small pandals or home altars. The idols are modest in size, but immense in heart. They are dressed in fresh flowers, surrounded by arugampul (Bermuda grass), and offered modakam—a sweet dumpling said to be Ganesha’s favorite. Sandalwood paste cools his broad forehead, and in many homes, turmeric-dyed rice is sprinkled around him like a halo of blessings.

Devotees don’t just worship—they talk to him. Tamil bhakti songs, often sung in local dialects, address Pillaiyar with the warmth of a beloved elder or a mischievous little brother. The music isn’t always grand or rehearsed. Sometimes it’s a soft lullaby, sometimes a playful tease. But always, it is sincere.

Temples such as the Ucchi Pillaiyar Kovil perched atop the Rockfort in Trichy, or the Manakula Vinayagar Temple in Pondicherry, become focal points of collective memory. These aren’t just architectural marvels—they are living spaces where faith breathes. People don’t just visit—they return, year after year, as one would to a grandparent’s home.

And this spirit of celebration doesn’t stop at Tamil Nadu’s borders.

Across the seas, in places where Tamil communities have taken root—Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, and even South Africa—Vinayagar Chaturthi blooms with the same devotion. In Kuala Lumpur or Batu Caves, one can hear Tamil prayers echoing through temple halls, blending tradition with new landscapes. In Singapore, vibrant Ganesha processions weave through Little India, while families gather for home prayers with the same clay idols and homemade sweets as in their ancestral villages. In Sri Lanka, particularly in the north and east, where Tamil culture thrives, Pillaiyar continues to be a guardian presence, especially in times of healing and hope.

What connects all these places isn’t the size of the idol or the volume of the celebration—but the feeling. The same warmth. The same familiarity.

Because whether in a small home in Sivakasi or a bustling flat in Singapore, Pillaiyar is always welcomed not just as a god, but as family.

To truly see Ganesha is to look beyond the idol. Because in Tamil tradition, every curve, every gesture, every object he holds—speaks. His form is not ornamental. It is instructional. Each part of his body, each companion by his side, carries a lesson for the soul.

His large ears, shaped like winnowing baskets, aren’t just an elephant’s trait. They remind us to listen deeply—to separate noise from wisdom, truth from distraction. Just as farmers winnow grain, letting the chaff fall away, so must we learn to filter what enters our minds.

His eyes, small and steady, speak of focus. In a world full of chaos, they remind us that true clarity comes from stillness. Not everything requires our attention—but what does, deserves our full gaze.

His broad head is more than a sign of power—it’s a gentle urging to think expansively. To hold space for diverse ideas, to embrace imagination, and to nurture curiosity. Tamil stories often say, “Think like Pillaiyar”—not big in ego, but big in thought.

Then there’s his vahana, the tiny mouse. At first, it may seem an odd choice—a giant god riding a small rodent. But the symbolism is elegant. The mouse represents the restless mind, always darting from one thought to another. Ganesha riding the mouse shows mastery—not by suppression, but by harmony. Even the smallest creature, even the wildest thought, can be guided with grace.

Around his waist coils a snake—a creature often feared. But here, it is not a threat. It is control. Discipline. The ability to hold one’s desires in balance. In Tamil temples, this is seen as a reminder: power lies not in indulging every impulse, but in taming it.

And finally, nestled in his palm is the modakam—a simple, sweet dumpling. It’s not just his favorite treat; it is a reward. A symbol of the joy that follows restraint, devotion, and spiritual effort. Like the fruit at the end of a long harvest, it reminds us that sweetness comes to those who walk with patience and purpose.

Together, these features form a map—not of the divine alone, but of the self. When a Tamil child gazes upon Pillaiyar, they aren’t just learning about a god. They are learning how to live. To think clearly, to act wisely, to listen kindly, to lead gently.

Ganesha does not thunder down from the skies. He doesn’t command from afar. Instead, he waits quietly—on doorsteps, in corner shrines, in the first line of a notebook, in the spiral of a suzhi. He teaches without speaking. He guides without leading. He is, and always has been, a mirror—showing us not only what the divine looks like, but what we might become.

Ganesha’s elephant-headed form, though cherished across many traditions, carries a distinct tenderness within Tamil culture. He is not just the remover of obstacles or the lord of beginnings—he is Pillaiyar, a name spoken with familiarity, affection, and quiet reverence wherever Tamil hearts have settled.

Across the world—in bustling cities and quiet towns, from Jaffna to Johor Bahru, from Batticaloa to Brickfields, from Durban to Dandenong—his presence weaves through Tamil lives like a sacred thread. He stands tall in carved stone at grand temples, and just as meaningfully, he takes shape in clay or cow dung, molded by hand during Vinayagar Chaturthi in home altars and community corners.

Whether recited in the verses of bhakti poetry, etched as a Suzhi in a child’s first notebook, or called upon before lighting a kitchen stove, Pillaiyar holds space in both the sacred and the everyday. He belongs to the learned and the layperson, the migrant and the monk, the urban and the rural—always adapting, always embracing.

In this way, Lambodara is not just a symbol of divine wisdom. He is a living emblem of Tamil identity—soft-spoken but resilient, rooted yet far-reaching, ancient yet always present. He moves where Tamils move, listens where they pray, and smiles quietly at the threshold of every new beginning.

As we come to the end of this journey, something gentle shifts. We begin to see Ganesha—not as a distant, divine figure frozen in time, but as someone closer, more intimate. Not just the elephant-headed god who removes obstacles, but a quiet companion through life’s winding path. A sacred presence who doesn’t command, but nudges. Who doesn’t dazzle, but reassures.

In the folds of Tamil tradition, Pillaiyar is not confined to temples or rituals. He lives in the everyday—in the rustle of prayer leaves, the curve of a child’s first scribble, the sweetness of a modakam shared, the spiral of a suzhi drawn with hope before a new task begins. He is the god who watches silently at thresholds, not asking for grand offerings, but for sincerity.

Through his form, he teaches without words. His large ears tell us to listen more. His broken tusk reminds us that imperfection can be sacred. His wide belly holds joy and sorrow together, without judgment. His little mouse whispers that no being is too small to be worthy. And his unhurried smile shows us the strength in stillness.

Perhaps this is why he has endured—not only in stories, but in hearts.

He does not change the world by force. He changes us, gently.

So the next time you pass by a Pillaiyar idol, nestled beneath a tree, painted on a temple wall, or quietly resting on a home altar, stop for a moment. Look beyond the clay and the color. Look into the meaning, into the memory.

Because he’s not just a god carved in stone or clay.

He is the wisdom of the elephant, the calm of the forest, the resilience in silence, the sweetness of devotion, and the spirit of a people who carry their faith not just in rituals, but in the rhythm of their lives.

All of that—and more—lives in one magnificent form: Lambodara.